This weekend, almost exactly a year after our return from Japan to Ireland, we’ll finally be moving into our new house. Our search for a permanent home in Dublin has not been an easy one, but that’s a story for another time.

Once again, our home is piled high with boxes as we pack up all our possessions ready for the move. The same boxes we used a year ago for the move from Japan to Ireland (in some cases, battered veterans of the earlier journey from Ireland to Japan) now find themselves reconstituted, taken out of flat-stored retirement and pressed into service one more time for the much shorter and easier move from Cabinteely to Leopardstown.

Houchigai jinja in Sakai city is a shrine that specialises in house moves. At the end of our recent visit to Japan we went there on our bikes to seek good luck and success in our forthcoming move.

The shrine was built 2000 years ago at the boundary of three ancient provinces: Settsu, Kawachi and Izumi. To this day, the area is known as 三国ヶ丘 Mikunigaoka, meaning 3-country hill. The tradition arose that as the shrine itself, being at the boundary and therefore not being part of any of the 3 countries, is not oriented in any direction, so a traveller by visiting the shrine could avoid unfortunate or wrong directions. The name 方違 houchigai reflects this tradition.

The water basin and well have old-fashioned characters written from right to left. The character for “country” in 三國山 is the same as I saw used in Taiwan; in modern Japanese writing it is simplified to 国.

Although the shrine is along the main road, it is a very tranquil place. Around the car park are camphor trees and a stand of wisteria, the trunk of which looks ancient and gnarled.

The shrine backs onto a wide moat surrounding a steep wooded island, which is a keyhole-shaped tomb or kofun, off-limits to human visitors.

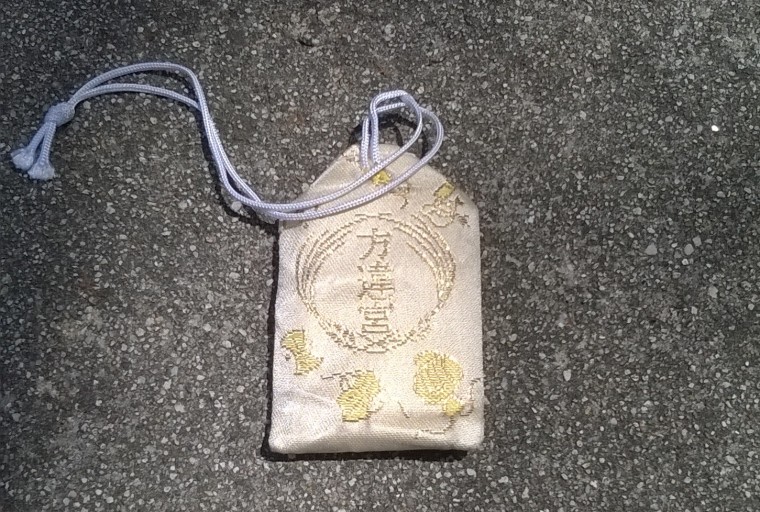

We brought with us a charm that we had bought on a previous visit to this shrine; a charm that had since then clocked up many air-miles and suffered much abuse in cargo holds and baggage carousels, as it travelled back and forth across the world attached to suitcase handles.

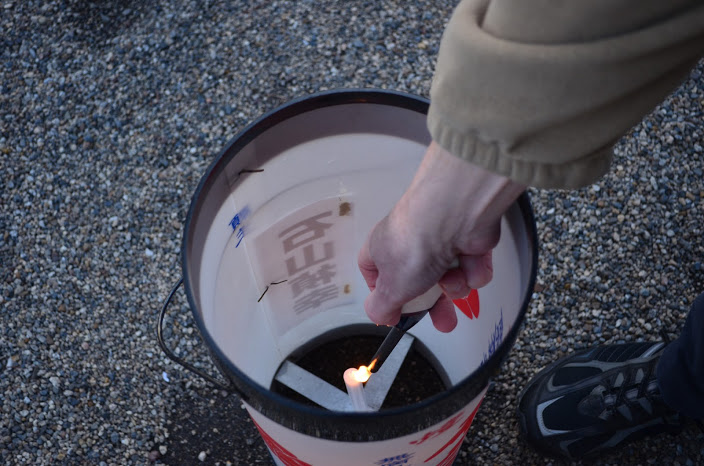

The tradition is that when a charm has done its job of keeping you safe, you bring it back to the shrine where it will later be destroyed in a special fire. For the moment it just gets dropped unceremoniously into this used-charm receptacle:

We bought an identical replacement charm for 500 yen, and then Yuko did o-mikuji.

Her fortune was good.