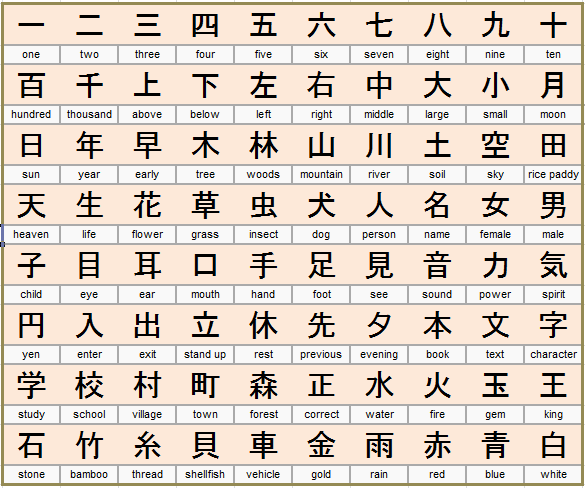

In your first year of learning Japanese, you probably learned the days of the week:

- 月曜日 Monday

- 火曜日 Tuesday

- 水曜日 Wednesday

- and so on.

And, with one exception, you will also have learned all the characters needed to be able to write these words; simple, Grade 1 kanji such as 日 sun, 月 moon, 火 fire, and 水 water. But the fly in the ointment is that tricky 18-stroke character 曜 you in the middle of each of the weekday names. Until you somehow get to grips with that, you may be able to read the Japanese word for Monday, but you won’t be able to write it.

Learning to write simple kanji is a straightforward matter of repetitively copying out the character until it is imprinted in your mind and muscle memory. Which is fine for the first 80, or maybe even 200. But over time you will have discovered that these simple characters are not typical, and that this method doesn’t scale well.

Fortunately, as you encounter more complex kanji, you will have noticed that many share features in common, and that those features suggest the meaning or sound. For example, the characters 痛 painful, 病 sick, 疲 tired, and 疾 shame all have the following feature in common: 疒. This “radical” or bushu*, known as やまいだれ yamai-dare, gives you a clue that the character means something to do with sickness. Other common bushu include radical 149 訁gon-ben, which appears on the left side of characters to do with speaking, radical 140 艹 kusa-kanmuri, which sits on top of kanji that refer to plants, herbs or vegetation, and radical 85 氵sanzui, which suggests a watery meaning.

There are 214 classical bushu in total, and during the past year I invested the time to learn each of them. Even the obscure, archaic and seemingly useless ones. Not just to recognise them, but (importantly) to write them. So was it worth it?

Well, let’s consider the character 曜 you, mentioned above. No longer is it a scary, seemingly arbitrary assemblage of 18 strokes; it is now a simple-to-remember construct of just 4 parts: 日 + 彐 + 彐 + 隹.

Each of those parts has a nickname, so I can describe it in words: nichi-hen, kei-gashira, kei-gashira, furutori. (sun, pig’s head, pig’s head, old bird. And remember that I’ve learned to write each of these parts, so it’s trivial to put them together and write the character. A character that, like so many others, I have been able to recognise for 20 years but would not previously have been able to write.

On the other hand:

- The bushu were not actually designed or selected for this purpose. They are not a comprehensive list of kanji building-blocks, nor were they ever intended to be. Their purpose is to be dictionary headings, to allow you to look up characters in the dictionary. Some very common building-blocks are not bushu, but are still worth learning. For example, 寺, which appears in characters like 詩 time, 待 wait, 持 carry, 侍 samurai, 特 special, and so on, usually giving a sound clue (“ji”) rather than a meaning clue. You really need to know those too.

- The list of bushu is not “efficient”; many of the bushu are themselves made up of simpler bushu. For example radical 186 香 ”fragrant” is made up of radical 115 禾 ”two-branch tree” and radical 72 日 ”sun”. This is okay though, as the more complex ones are often kanji worth remembering in their own right.

- Some of the simplest radicals are just lines or dots, with limited semantic content.

- Some of the bushu are utterly obscure. For example you will almost certainly never meet any kanji containing radical 35 夊 sui-nyou “go slowly” or radical 191 鬥 tatakai-gamae “war”. But I’m a bit of a completist, so I learned them anyway. And in the case of radical 192 鬯 nioi-zake “sacrificial wine”, it paid off (see below).

But the day I knew it was worth it was when I noticed that I could now write the following famously-difficult character:

From being an absurdly complex and impenetrable mass of lines, it now resolves itself as just six parts to remember, each of which I already know how to write: 木 缶 木 冖 鬯 彡(tree, can, tree, cover, sacrificial wine, hair).

So why learn bushu? Four reasons:

- They’ll give you clues to the meaning of the kanji

- They’ll give you a short cut to remembering new kanji, without having to explicitly learn them

- They’ll make your knowledge of kanji more precise (for example, allowing you to clearly distinguish similar kanji)

- You need them to be able to look up characters in an old-fashioned dictionary (does anyone do that anymore?)

And maybe a 5th reason, if you’re anything like me:

5. It’s kind of interesting in its own right and gives you more insight into the writing system.

Is it worth learning the bushu during your first few years of learning Japanese? I’d say almost certainly not. You can put your time to far better and more enjoyable use learning vocabulary and grammar, listening, speaking and reading the language. But later—maybe much later—you may come to feel, as I did, that your knowledge of the kanji is built on a somewhat shaky foundation; that you can recognise many kanji in context but you don’t really know them; that you still get confused between kanji such as 通 and 進, or 速い and 遠い (or worse, you never realised that 着る kiru—to wear and 着く tsuku—to arrive are the same kanji!) And you’ll want to go back and consolidate your knowledge, deepen your understanding. And when that time comes, you could do worse than set aside some study time to learn the bushu.

* The word 部首 bushu literally means “section head”; each radical sits at the head of a section of the dictionary, and that’s how you look up the character in the dictionary. They are known as the “Kang Xi” radicals after a dictionary of 47,000 characters published in 1716 on the orders of Chinese emperor Kang Xi, and they still form the basis of paper dictionaries in Japan and China to this day.